Oral Language Supports Writing Development: How Bolstering Conversations Builds Power and Voice

Published Tuesday, October 28, 2025

Advancing Literacy

Kids arrive at school brimming with ideas and stories. As they tumble into classrooms, their daily conversations with classmates and teachers serve as a powerful rehearsal for writing. They share stories, offer opinions, and teach each other new things—all essential elements of communication. Writing, much like conversation, is an expressive tool for conveying thoughts, ideas, and experiences.

Oral Language is a Key Component of Successful Writing

Translating ideas from our minds to the page is a complex process. To understand this complexity, it’s helpful to consider frameworks and writing models like The Writing Rope (Sedita, 2019). In this framework, Sedita illustrates that developing powerful young writers requires attention to several key areas:

Critical Thinking

Syntax

Text Structure

Writing Craft

Transcription

The integration of these five strands is a challenging task that places a significant cognitive load on the brain. As educators, parents, and caregivers, our role is to remove barriers and create supportive, purposeful opportunities for students to engage in the writing process. We can do this by providing scaffolds, teaching specific skills, and encouraging students to work through productive struggle.

Bolstering oral language development is a necessary and effective way to support young writers. Studies have shown that strong oral language skills, combined with transcription skills, directly improve the quality of a student's writing (Kent et al., 2014). Oral language provides a foundational scaffold that students can use to build their writing skills before, during, and after they write.

Talk Before Writing to Support Idea Development and Organization

Whether students are writing in school or at home, in the literacy block or in math, encourage them to talk before they write. Talking, or oral rehearsal, helps people generate and develop their ideas, sparking more of what they want to say. When they can focus purely on the message, without worrying about spelling or punctuation, their language and ideas flow more freely. This pre-writing process reduces the cognitive load on the brain, freeing up mental energy so the student can focus on the complex task of putting words onto the page after they have had a chance to rehearse through talk or conversation.

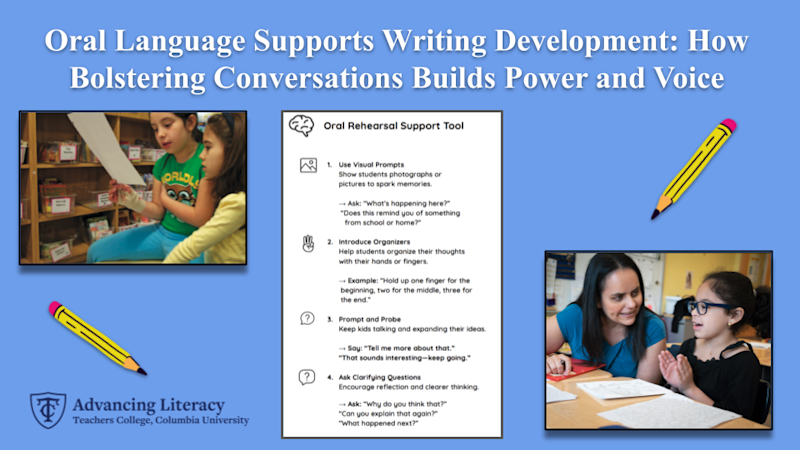

Some effective ways to coach writers to use oral rehearsal include:

Use Visual Prompts: Visuals provide a concrete foundation for idea generation. Looking at photographs or pictures together helps to spark memories and stories about family or school experiences.

Introduce Organizers: Encourage kids to tell stories, share information, or make arguments using their hands or fingers to mentally organize each part of what they want to say.

Prompt and Probe: Simply ask children to tell you as much as they can about what they want to write. Use open-ended prompts such as, “Say more about that,” or “That sounds interesting, keep going.”

Ask Clarifying Questions: Use questions to encourage reflection and expansion. Asking questions such as, “Why...?” or “Can you explain that again?” helps kids clarify and elaborate on their thoughts and ideas.

Whether they use images, their hands, or extended conversations, all of these tools help kids discover and structure what they have to say.

Talk During Writing: Support Idea Development, Clarity, and Precision in Writing

Oral language is equally valuable during the drafting process. As a writer puts ideas onto the page, the cognitive load escalates—the brain must simultaneously choose (and spell!) precise words, construct grammatical sentences, and build cohesive paragraphs. Using talk and conversation while writing is a key component to remove these complex barriers.

Here are effective ways to coach writers to use talk and conversation as they write:

Verbalize Sentences: Ask students to verbally say the sentence they want to write several times, in advance. This practice helps them find the most precise words and refine the syntax before they attempt to put words on the page.

Read Aloud Frequently: Encourage kids to frequently reread what they have written, especially out loud. Hearing their work allows them to catch missing ideas, recognize awkward phrasing, and often generates new thoughts to add or expand upon.

Build a Culture of Collaboration: Writing partnerships can change the learning culture. Collaboration enhances relationships and promotes a sense that learning belongs to the entire community (Hammond, 2015), making the rigorous task of writing less isolating and more supportive.

Talk After Writing: Support Revision, Self Assessment, and Reflection

Conversation remains a powerful tool even when a draft is “finished”. Talking about a completed piece helps a writer break down the many aspects of their work and gain valuable insight into their process and learning.

Reflecting on their work allows writers to assess their progress and set new goals. Asking writers to name their intentions—“I tried to make this part funny,” or “I wanted people to see how important ____ is.” This promotes metacognition and helps young writers get a sense of when and where their work will benefit from revision.

Here are effective ways to coach writers to use talk and conversation after they write:

Reflect on Intent and Learning: Ask questions that help the writer reflect on their original goals:

“What were you trying to show or teach in this piece of writing?”

“What did you learn during the process, and what do you want your reader to walk away with?”

Talk Through Key Parts: Engage the writer in a discussion about specific sections to encourage self-assessment:

“Let’s talk about the part that is most important to you.”

“Which section do you think needs more work?”

Focus on Craft and Language: Ask the writer to read one sentence aloud and explain their choices:

“Why did you use the word ‘rushed’ instead of ‘went fast’?” This prompts reflection on vocabulary and craft.

“What details are important to include?”

Talk Through Revision Ideas: Shift the focus from critique to possibility by discussing options:

“What are two or three different ways this piece could end?”

“Where could a new detail be added to make the message clearer?”

Share Reader Impact: Have a conversation about what you, as the reader, learned or gained from the writing. Discussing the work from a reader’s perspective helps the writer see how their ideas impact others and strengthens the connectedness between writer and audience.

When we intentionally integrate talk before, during, and after writing, we help students utilize and develop their oral language skills that, in turn, support the complex demands of writing. This practice helps kids see the great potential in their voice and ideas, building both skills and confidence. By engaging as learning partners, peers, teachers, family members, and caregivers, we strengthen the bonds that foster a collaborative learning community. Writing is, ultimately, an expressive tool that allows students to share their unique perspectives, knowledge, feelings, experiences, and humanity with the world, which in turn has the power to bring people closer together.

References Hammond, Zaretta, and Yvette Jackson. Culturally Responsive Teaching and The Brain: Promoting Authentic Engagement and Rigor among Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students. Corwin, 2015.

Kent, Shawn, et al. “Writing Fluency and Quality in Kindergarten and First Grade: The Role of Attention, Reading, Transcription, and Oral Language.” Reading and Writing, vol. 27, no. 7, 2014, pp. 1163–88, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-013-9480-1.

Sedita, Joan. The Writing Rope. Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co, 2023.

Tierney, R. J., & Shanahan, T. (1991). Research on the reading–writing relationship: Interactions, transactions, and outcomes. In R. Barr, M. L. Kamil, P. B. Mosenthal, & P. D. Pearson (Eds.), Handbook of reading research, Vol. 2, pp. 246–280). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

York, Carnegie Corporation of New. “Writing Next: Effective Strategies to Improve Writing of Adolescents in Middle and High Schools.” Carnegie Corporation of New York, https://www.carnegie.org/publications/writing-next-effective-strategies-to-improve-writing-of-adolescents-in- middle-and-high-schools/. Accessed 15 Oct. 2025.

References

Hammond, Zaretta, and Yvette Jackson. Culturally Responsive Teaching and The Brain: Promoting Authentic Engagement and Rigor among Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students. Corwin, 2015.

Kent, Shawn, et al.. “Writing Fluency and Quality in Kindergarten and First Grade: The Role of Attention, Reading, Transcription, and Oral Language.”. Reading and Writing, vol. 27, no. 7, 2014, pp. 1163–88, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-013-9480-1.